You have a wealth of background experience to pull from in the work you do now. We hear you like to play in the dirt. What was your experience as an archaeologist like?

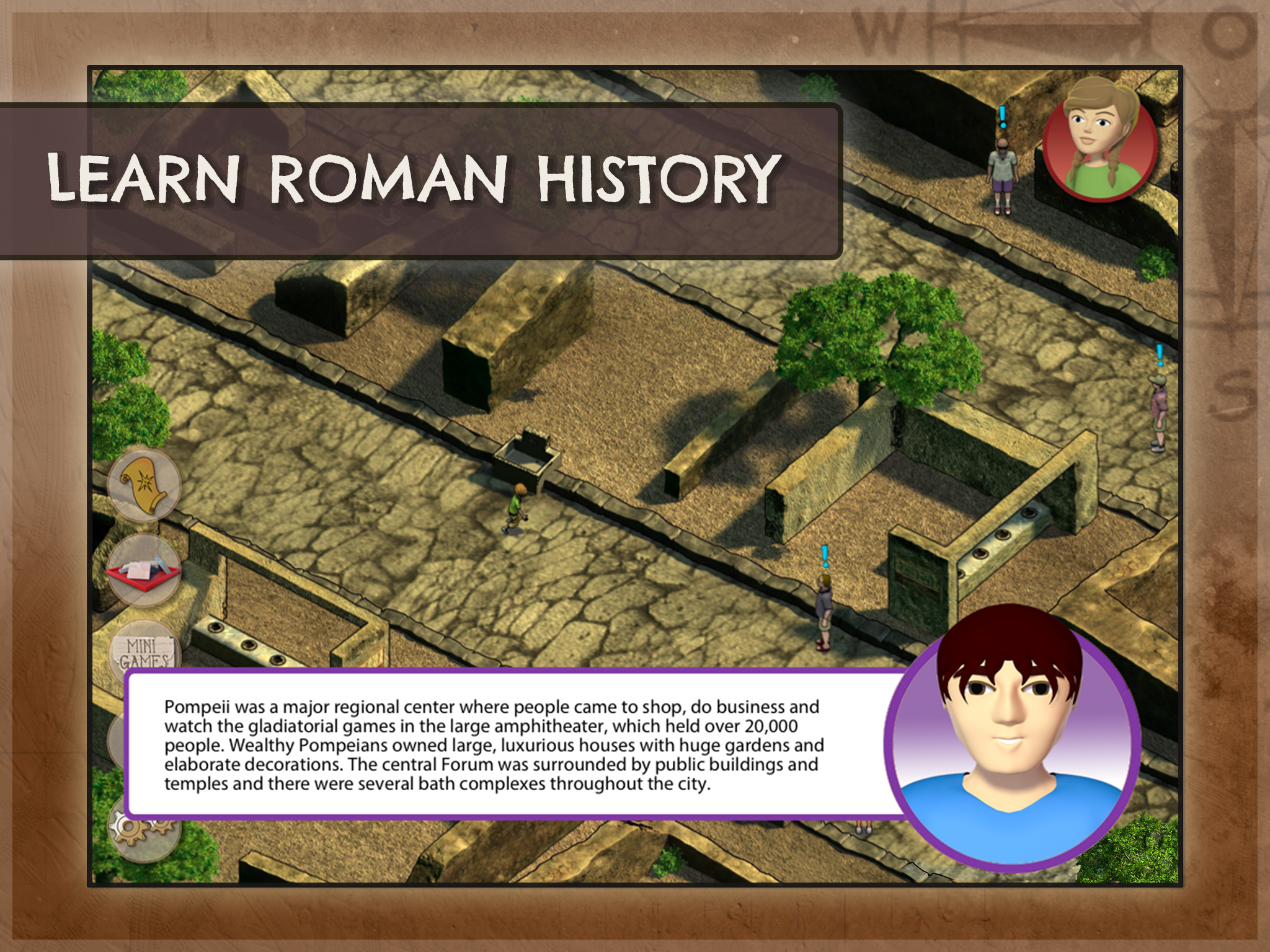

One of the things I liked most about fieldwork was the opportunity to be in another country for an extended period of time. I loved getting the chance to actually experience the culture in a way you really can’t when you’re just visiting for a few days. I do have to admit though, I liked the dirt a lot too! I’m one of those weird people that actually likes studying dirt layers. Finding cool artifacts is fun, of course, but it’s the dirt that really tells the story. Archaeology is all about every day life—artifacts tell us what people ate, what they wore, and how they spent their time. But it’s the dirt that tells us when and how people used those things. Archaeology is pretty hard work—all that dirt is HEAVY!—but it was all worth it to see first hand how people lived in the past.

How did your past experience as a social studies teacher help you in the transition to game designer?

It does seem like teacher and game designer are really different, doesn’t it? Surprisingly, they’re not. A big part of games, especially the kind we make, is teaching something. Even games that aren’t strictly for learning have to teach players how to operate in their world. The fancy word for it is “user interface,” but really, it’s not so different from planning lessons that will engage your students. The goal with both is to communicate information quickly and easily in a form that resonates with your audience. Then you have to figure out how to seamlessly build on that knowledge through the course of a game, kind of like planning a class. Levels are very comparable to units in that knowledge of a specific feature set builds slowly through the level and completing the level shows mastery the way an end of unit test does. Even grading has a place in game design: when you really think about it, grading a test and scoring a level are virtually the same thing—they communicate the level of mastery for the content. Good games, like good lessons, require deep understanding not only of the game content but how the user will respond to it. In that, game designers do have an advantage over teachers. Feedback in games is immediate and leveling up requires full mastery of the content. That allows game designers to communicate directly with the player and know instantly when a feature does its job successfully.

Do you have any advice for teachers looking to implement more digital games in the classroom?

Teachers have always known that games add depth to lessons by engaging students’ imaginations and allowing them to find answers on their own and in their own way. Games on mobile devices, computers, and interactive whiteboards combine graphics, audio, and movement into a coherent whole. These games are interactive and immersive, forcing the player to be truly invested in the outcome. Players are encouraged to strengthen weaker skills while simultaneously taking advantage of their proficiencies. For teachers looking to add digital games in the classroom, there are a few common denominators found in successful interactive learning games, such as being authentic and skills-based. Teachers should consider how different games can be woven into the curriculum based on content. For example, reinforcement games can be played just after students have begun to master new skills. Most importantly—teachers should show their students that they’re excited about adding games into the classroom; when teachers are excited, students are too. Just like playing digital games, enjoy blending fun and learning in the classroom with the addition of these tools to your curriculum!