Get ready for a STEAM-infused summer! The integration of the Arts into STEM adds a dash of creativity into summer learning. Here are just a few of our favorite STEAM projects for you to play with. This list is perfect for parents looking to keep their kids engaged over the summer months—and have fun while doing it!

Looking for something more hands-on? Check out our kite-making activity below, created by FableVision’s Christina Kelly!

Geniverse, Concord Consortium

Geniverse is a free virtual lab environment that allows students to learn about biology through interaction and experimentation. In Geniverse, students are able to investigate dragon phenotypes and genotypes, run breeding experiments, and solve genetic problems. Geniverse encourages students to have fun while learning biological concepts through interaction with mythical beasts but each concept is rooted in science and can be directly applied to both the classroom and the real world.

Good Thinking! The Science of Teaching Science, Smithsonian Science Education Center

Good Thinking! is an engaging and entertaining free web series designed to enhance K-8 science education, and deepen understanding of STEM topics for teachers and students alike through exploration of pedagogical ideas across a range of subject-matter topics like energy, natural selection, and gravity, as well as cognitive research findings on topics such as student motivation, or the myth of left- and right-brained people. Each episode has been vetted by experts and adheres to next generation science standards.

Weather Lab, Smithsonian Science Education Center

Weather Lab is a free online game that allows players to select different ocean currents and air masses that visualize the result of the combination. As a tool used in classrooms, care was taken to ensure the correct symbols and movement of air masses correspond with the weather pattern and land at the exact point on the map. Teachers use the Weather Lab to encourage students to think critically and make predictions. The overall goal is to teach students about the relationship between climate and how it affects them on a personal level.

Zoombinis, TERC

In Zoombinis, players test their logical reasoning, data analysis, pattern finding, and problem-solving skills as they help Zoombinis complete unique challenges. Through Zoombinis, players learn important life skills including algebraic thinking, data analysis, and theory formulation in a fun and engaging setting. With 12 puzzles and four levels of increasing difficulty in each, players are constantly challenged, improving their problem-solving skills as they advance through the game. Hip, hip, Zoombinis!

Sid the Science Kid, Jim Henson Company/KCET/Los Angeles for PBS Kids

The website created for Sid the Science Kid allows 3-5 year olds to explore and practice scientific methodology through several games that integrate progressive learning and open-ended play. The site encourages collaborative learning between adults and children by providing interactive teachable moments that extend the learning within each game. The Parent/Teacher sections contain free extensive information about the show and the website, and they provide resources to aid adults as they explore science and help answer their children’s questions.

Renegade Buggies, National Center for Families Learning

With retail wrapping, Renegade Buggies encourages free financial and mathematical literacy for the whole family. By combining gaming with money management skills, Renegade Buggies is a fun way for both children and parents to learn basic budgeting skills. The game has four levels: unit prices, buying in bulk, coupons, and promos. The entertaining gameplay meets the educational goals seamlessly, and customizations up the fun factor: visit the virtual body shop with your earned coins for a stunt suit, bunny ears, and more!

Fab@School Maker Studio, FableVision Learning

Fab@School Maker Studio is an easy-to-use web-based digital design and fabrication tool that invites students in grades 3-8 to experience STEM and STEAM learning in a more engaging, personally meaningful way. Fab@School Maker Studio offers a unique on-ramp to engineering with cross-curricular activities ranging from simple to sophisticated. The program supports a variety of materials and a large set of tools from scissors, rulers, and pens to 2D cutters, laser cutters, 3D printers, and more!

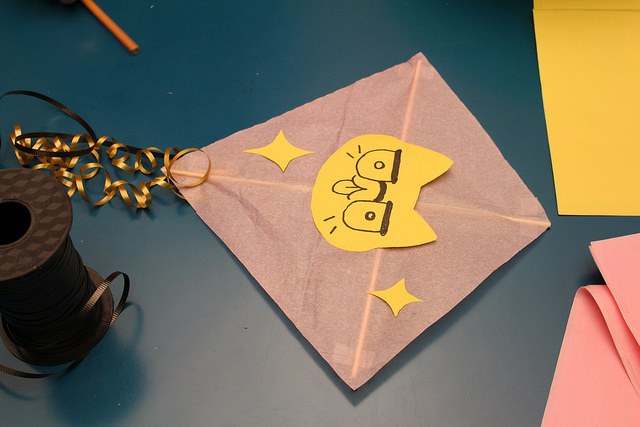

Get Crafty with Christina Kelly, FableVision's Production Designer!

Collect your supplies. You will need:

- Tissue paper

- Tape

- 2 wooden dowels

- Scissors

- Ruler

- Markers

- Ribbon for the tail

- String

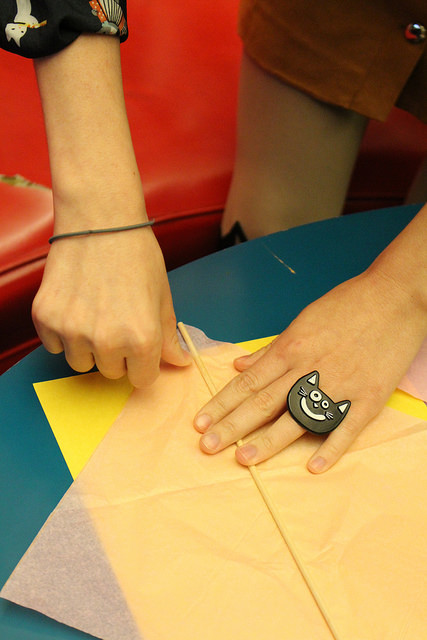

1. Sketch and cut your kite sail

Fold the paper in half and taking a pencil, trace a half diamond the length of your dowel. Carefully cut out the shape and unfold your paper.

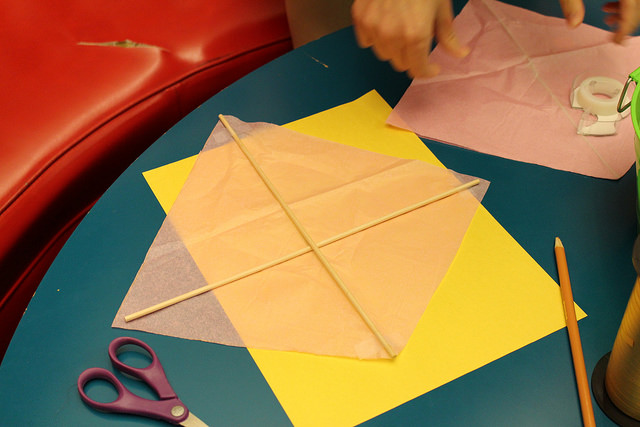

2. Build your kite structure

Take your wooden dowel and lay it down the center of your sail, from the top of the diamond to the bottom. Tape at the ends to secure the dowel to the sail. Take the second dowel and lay it down to form a “t” with the first piece. Tape the ends together.

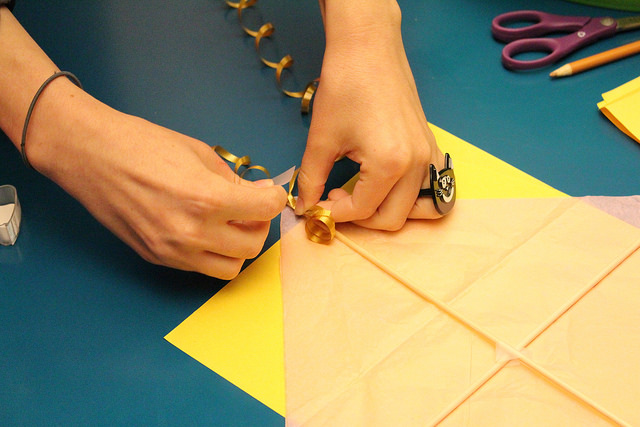

3. Make a tail

Using your ribbon, add a few tails to your kite. For a fun look, you can curl the ribbon with your scissors. See directions here to learn how.

4. Attach your line

Take the string and tie it to the right and left hand sides of the horizontal stick. Then tie the string to the center of that string for your flying line.

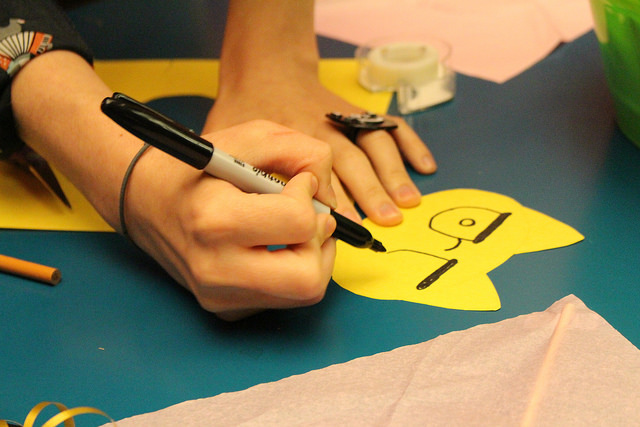

5. Decorate your kite

Add a dash of personality to your kite! I really like cats so I’m making my kite a purr-fect blend of kittens and pizzazz.

6. Go out there and fly your kite!

You’re ready! Just find a strong breeze and watch your kite soar!